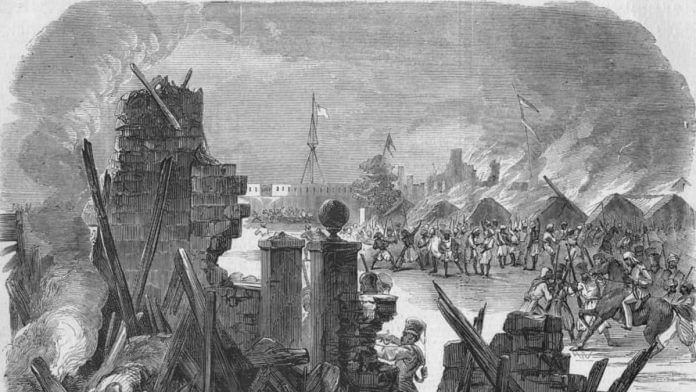

On this day in 1857, how ‘punishment parade’ in Meerut lit spark of 1st war for Indian freedom

85 sepoys of 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry were charged with mutiny, shackled, and paraded to jail through the streets of Meerut on 10 May 1857.

New Delhi: On 10 May 1857, 85 sepoys of the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry were charged with mutiny, shackled, and paraded to jail through the streets of Meerut.

This punishment parade came in reaction to the events of 24 April 1857 — a day of immense significance in India’s freedom struggle, as it symbolised the first open and collective defiance of British rule by Indians.

Central to the events of 24 April was the refusal by sepoys of the 3rd Bengal Cavalry to use the newly introduced Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifles, owing to prevalent rumours that the cartridges of these rifles were greased with pig and cow fat. The cartridges needed to be bit open to be loaded, and the rumoured use of animal fat as grease hurt the religious sensibilities of both Hindu and Muslim sepoys in different ways.

On the 165th anniversary of the 10 May punishment parade, ThePrint takes a look back at the events of the first war of India’s independence.

Also read: After 1857 rebellion, Delhi properties of ‘disloyal’ Indians were confiscated

The legend of Mangal Pandey

Dissent and discontentment with the British superiors was brewing in the army even before the events of 24 April.

Outraged by the rumoured use of cartridges greased with cow and pig fat, on 29 March 1857, Mangal Pandey — popularly remembered as Amar Shaheed — a sepoy of the 34th Regiment Native Infantry, reportedly dressed in the regimental red jacket and a dhoti (instead of platoon pants), entered the parade ground of the military cantonment in Barrackpore, where he was then posted, and fired at the first English officer he could see, Sergeant-Major James Hewson.

While Pandey’s shot did not hit the target, the commanding officers instructed the other sepoys to restrain him, an order which they disobeyed. However, the other sepoys ignored Pandey’s calls to attack the foreign officers at the time, and did not join his revolt.

But as punishment, the entire regiment was disbanded. Pandey was taken to trial within a week of the events at Barrackpore and received a sentence of execution on 18 April 1857. The date was, however, advanced and he was executed on 8 April.

News of the events of 29 March, the rumours about the cartridges and the disbandment of Pandey’s regiment, spread to other parts of the country, and sepoys in other regiments and units of the army felt alienated and frustrated with the British.

The mutiny of 24 April 1857

Resentment against the British kept building, and finally boiled over on 24 April 1857.

Lieutenant Colonel George Carmichael-Smyth was the commanding officer of the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry at the time.

As Colonel Patrick Cadell (a member of the Indian Civil Service) noted in the Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Carmichael-Smyth was the “eighth and the youngest of a string of brothers, who were in the service, civil and military, of the crown or of the East India Company”.

On 24 April, as dissent among Indian sepoys continues to grow, Smyth took matters into his own hands and decided to show them the use of the new cartridges.

As John Campbell Erskine, a Cornet in the 3rd Regiment of the Bengal Light Cavalry, noted in a letter — “Colonel Smyth injudiciously ordered a parade of skirmishers of the regiment to show them the new way of tearing the cartridges”.

Out of the 90 sepoys he ordered to tear open the cartridges, 85 refused, resulting in the first open mutiny against the British authorities.

The parade was dismissed and a court of inquiry was held in Meerut.

They were consequently held guilty of mutiny on 10 May and were “sentenced to 10 years on the roads in chains!”, wrote Cornet Erskine. The “10 years on chain”, was a figure of speech to mark the hard labour they would be subjected to in prison.

Mutiny & the siege of Delhi

After the sepoys were shackled and imprisoned, there were protests across Meerut.

According to the British Parliamentary Papers on the Indian Mutiny 1857, shortly after their imprisonment, a party of the 3rd Light Cavalry went to the jail and released their imprisoned comrades. Soldiers of the 20th Native Infantry who were supposed to guard the prison offered no resistance.

What followed was a mutiny — or what is now called the first war of Indian independence — with uprisings in Lucknow, Kanpur, Jhansi, Indore and Arrah in Bihar.

Scholar A.H. Amin wrote in the Defence Journal that the sepoys of the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry, after escaping from the prison, marched 40 miles to Delhi and seized the capital. The sepoys held fort around Delhi, encircling the city from July to September 1857.

However, by September 1857, the British forces had gained the advantage and re-captured the capital.

Amin added that the sepoys “withdrew to Lucknow after the fall of Delhi in September 1857 and then to the Nepali Himalayan region of Terai in March 1858”.

Most of the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry men either died fighting or because of disease and starvation in Nepal. Some of the sepoys returned to their homes in Rohtak and died in poverty, ironically, alienated by society for standing up to the British.

While the 1857 war didn’t fulfil its larger goals of emancipation from colonial rule, it lit the spark which eventually gave fire to the larger struggle for independence.

(Edited by Poulomi Banerjee)

Also read: Don’t remember the 1857 Mutiny with Rani of Jhansi alone. You’re missing out on Uda Devi